Directing Your Film

Directing for Film

Who is the Director?

The director is the boss on set. They have the final say on all creative matters of the production, from how the film is shot, to how the actors move and speak in front of the camera. The director does not worry about budgets, scheduling, or marketing. They are distinct from a producer. Rather, it is their job to bring a script to life visually, from being on-set to the final changes in the editing room.

Directing Film vs. Directing Theater

There are many parallels between directing for a film production and a theater production—and many directors dabble in both—but there are major distinctions. In both mediums, the main goal is for the director is to help the actors give the best performance possible. You want them to full portray these people discovered by the writer, in turn, a director wants to translate these performances into emotions and an experience felt by the audience. In film, this takes on a different level of responsibility, as this action takes place in front of a camera.

As a film director, your main goal remains the same: to have your film effectively convey the emotions and themes you have interpreted from the original paperbound screenplay. A film director accomplishes that with the balance of two tools: powerful visuals and performances*. The following sections have tips on how a director should navigate both the visuals and the actors while working on a film.

Pre-Production

Note: Many aspects of pre-production occur concurrently

Finding Your Take on a Story

One of the most important parts of being a director is knowing the story that you want to tell. If you are writing the film you are directing, than you are the one with the most intimate information on the characters and the plot. If not, it is important that you meet with the writer as early in the process as possible. Read the script, ask many questions, and get as much of a feel for the world of the characters—and the characters themselves—as you can. Even if it’s your story, writing out these questions for yourself can be a great way to start thinking about how to present the film. You should be able to walk out of those initial meetings with the ability to watch the movies play out in your head.

Note: When perusing the YFA website for directing opportunities, look at stories that you are connected to. Never do a film you don’t feel something for or one that you can’t see in your head. An uninspired director = an uninspired film.

Finding/Meeting a Producer, Director of Photography, and Storyboards

Below are two key team positions that a director must work with before other crew is assembled.

Producer

In many cases, you will have already been in contact with the Producer, who is essentially the business manager of your film (Tip: You need a producer, there’s no way getting around that. It’s your job to focus on the creative elements of the film). Other times, if it’s your own project, you will need to find one by using the YFA opportunities page. In certain cases, as with Bulldog Productions, an organization will help you find a producer and other essential crew.

You should meet with the producer as well once you have a vision for the story. They will be able to sit down and talk to you about what is realistic, what you need in terms of a production team etc. They will help you put the rest of your team together and will supervise your shoots to make sure they run smoothly.

Director of Photography

The Director of Photography, or DP, is the person you will depend on to capture the shots you set up. It is their job to translate the visuals you want into camera framing and composition. As you will be working with smaller crews than the real world, your DP can also be considered your camera person.

As with your producer, you should be meeting with your DP very early. With them, you should come up with either a shot list or a storyboard.

Create a Visual Roadmap

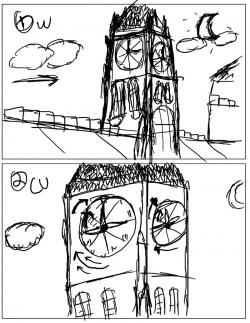

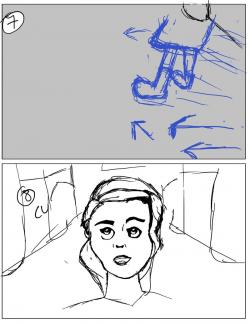

Shot-lists & Storyboards

A shot-list is a spreadsheet that organizes every major shot set up in your film and helps you break the film into visual chunks. It generally contains a scene number, a shot number, the type of shot (i.e. close ups, wide, etc.), and shot or scene description. However, when working with your DP, you might want to have a better way to show and share visual ideas. This is what a Storyboard is for. A storyboard is best described as comic-strip of your film, showing all of the shots and action in a series of still images. Below are examples of shot lists and storyboard. There is no one way to these:

Equipment

While this is primarily a job for your DP, it is also wise to figure out early on the technical details of your film. Now that you know what shots you want, you need to know what kind of equipment you will need. You can borrow equipment from the Bass Media Equipment Checkout catalog including cameras, tripods, and accessories you can use to make your film.

Locations

While creating your visual roadmap, you should also be communicating with your producer about potential locations for scenes in your movie. Those need to be scheduled and discussed as soon as possible. Also, be realistic.

Casting

For more information on the casting process, see our Casting how-to.

Prepping Actors for Roles

At the First Read-Through

A read-through is where the actors, director, and any other principal members of crew sit around a table and read through the script from beginning to end.

As a director, this the rare time where you give no direction. At the read-through, listen to the actors, take extensive notes, but don’t give criticism or ideas. You should take those ideas into rehearsals and table work.

Rehearsals and Table Work

While it is not required for your actors to memorize the entire script in one clip, you should be holding rehearsals leading up to production so that they are familiar with each scene. Rehearsals also allow you to really spend the time working with actors on getting the emotions and head spaces required for their eventual performances on camera. There are two distinct kinds of rehearsals that are at your disposal and come in handy for tackling different directorial problems:

Table Work: table is what it sounds: sitting at a table, going through the script. However, unlike a read-through, the director should be going scene-by-scene and giving the actors notes. This is also the time where you hash out issues like back-story, motivation, and general character questions. Table is work is about content and delivery, not blocking. This can be done one on one with a director.

General Cast Rehearsal: This is where multiple actors are in the space together and are moving and interacting with one another. Here is where you hone in their relationships and interactions. This is also where you can talk about general blocking and where actors will stand and move in the space in relation to others. This depends on your location, but you should be thinking about general motion and shot set-up in rehearsal space.

You should be having rehearsals throughout pre-production, and should aim to work through the script at least twice, depending on your how long pre-pro lasts.

Production

Come to set prepared

A director should always come early to set (i.e. when the production team is called).

A director should always have their shot list (as should their Assistant Director)

A director should always have a copy of the script.

Shooting a Take (the procedure)

While crew is setting up the shot: Talk to your actors. Walk them through the blocking for the scene, set their motivation. If you have a small crew, help set-up, but make working with the actors your priority.

While people move to positions for take: Head to your DP. Make sure the camera is set up the way you like and that they understand how the shot will work and what they need to capture. Stay by the camera/monitor: You should be splitting your time between watching the actors in real time, and watching the camera/monitor.

When everyone looks ready: You make the calls. The calls are as follows, in order:

When everyone looks ready, you make the calls. The sequence of calls is as follows:

“Camera Rolling?”

- Response from DP: “Rolling.”

“Sound?”

- Response from Boom Operator/Sound Mixer: “Speed.”

“Mark.”

- Translation: Someone moves the slate into the camera to identify the film, scene, shot, and take.

- Response from Slate (Asst. Camera): “[Title of Film], Scene [Number], Shot [Number], Take [Number]”

“Action.”

- The shot begins. Once the shot reaches the end, wait a moment, then call:

“Cut.”

- Response: Camera stops, sound stops, everything stops.

The minimum commonly used set of phrases for calling the roll:

- 1st Assistant Director: “Quiet on set! Roll sound.”

- Sound Recordist: “Speed.”

- 1st AD: “Roll camera.”

- Camera Operator/Cinematographer: “Rolling.”

Then, the 2nd Assistant Camera (2nd AC) (or 1st AD if no 2nd) will slate with the clapperboard and call out the scene and take numbers (e.g., Scene 45, Take 5). The clapper is used to sync the audio and video media.

- Camera Operator/Cinematographer: “Set” (when the camera is in position and focused).

- Director or 1st AD: “Action.”

- After the take is complete:

- Director: “Cut.”

When everyone stops:

- If there are any technical problems (i.e. shot was unfocused) bring those up.

- Get out from behind the camera. Give the actors notes if you have any.

- Decide if you want another take

- If not, cross it off on your shot list and set up for the next shot

- If so, call “reset” and set up the shot again.

How long should a shot be?

You shouldn’t be shooting entire scenes in one shot or take (unless that is a visual style in your movie). Shots are smaller chunks of a scene that represent one possible angle. They should be cut up into manageable chunks that the actor’s can manage. Another way to cut up a scene into shots is by finding where the logical “periods” are in the scene (I mean this (.) kind of period). For example, an awkward pause in a dinner scene would be a great place to cut a take of a particular shot. In poetry and music, these abrupt stops are called caesuras; they also exist in film and are a great tool for directors to use.

Directing Actors on Set

When giving actors notes on set, it is important to be direct, concise, and non-prescriptive. Get to the point and be assertive, correct egregious errors, do not overwhelm them with notes, and most importantly, don’t just tell them how to act. Your goal on set is to lead them to the ideal performance, but they have to get there are their own. If you are having trouble doing so, try going back to discussing character motivation and what the character wants in that scene.

Making your days

Like a theater performance, being on-set has a start and end time (referred to as wrap). Your producer and assistant director are the ones watching the clock to make sure you do not go over that time. As a result, you have very little time to get a lot accomplished. Often you will have to make decisions that favor certain aspects of the production over others, depending on what you have time to do. This can include:

- Limiting the amount of takes you are able to have of each shot

- Limiting the number of scenes you can get finished each day

- Choosing exciting visuals over performance and vice versa

- Having extra footage like establishing shots of spaces

There is no clear answer on what to decide, only the question: What do I feel (as the director) is essential to telling the story the way I envision it? Anything that doesn’t fall under that category should be able to be cut for time. Once again, be realistic about what you need and can accomplish.

You can go over wrap time sometimes, but it’s not something to make a habit of in the process.

Post-Production

For directors, you should be scheduling meetings to review footage with your editor. Unlike with your actors, you should be giving them specific notes about what shots you think work, and the logical flow of the story. You have final cut, which is approval over the final version of the film that will be screened to an audience.

General Directing Tips

Remember, you are the one in charge on set. Even if everything is falling down around you and everyone is in panic, remain calm. With great power comes great responsibility.

You catch more flies with honey than with vinegar. However, at the same time, be assertive and a voice of decision. As a director, you are required to make fast decisions with confidence.

Have fun! Directing is an incredible experience, as you are literally watching your imagination come to life.

For any further questions on directing film, please email us at yalefilmalliance@gmail.com.

Happy Filming!

Written by

Travis Gonzalez (TC’16)

* You kind of need to be the Avatar.